Nuanced Climbing Anchors

In rock climbing, regardless of how hard or high, we have to at least consider attaching ourselves to the mountain. Generally speaking, our belay anchors provide that sort of ultimate security. Climbers study their anchor-building skills and have excellent resources for that. Countless books and classes are offered. The concepts are reasonably simple and the procedures build in a safety factor to accommodate less-than-stellar application of the gear and techniques. In short, most climbers build good belay anchors. That doesn’t mean we can’t continue to improve. In that vein, let’s do some “continuing education”.

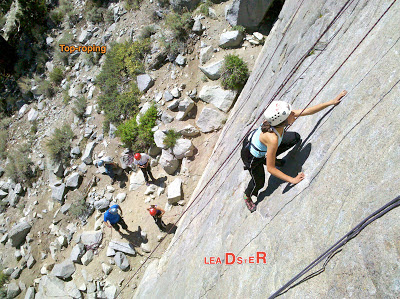

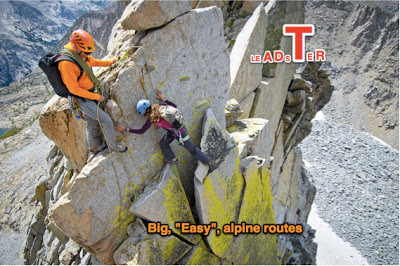

First of all, you probably learned to assess belay anchors with an acronym prompting your thought process. This blog has outlined the etymology of the most commonly-used acronym, SERENE. (Solid/Strong, Equalized, Redundant, Efficient, No Extension). Others have proposed what I deem a slightly more applicable “grading” rubric: LEADSTER. (Limit Extension, Angles, Direction, Strong/Solid, Timely, Equalized and Redundant). I know, it is a subtle difference. However, the inclusion of prompts for considering angle between protection pieces and the associate forces, as well as all the possible directions of pull on the anchor can really help each of us address the most common anchor-building short-comings. Try it out.

LEADSTER works well to critique any rock climbing belay anchor. Applied correctly, with the proper equipment and skills, this checklist will assess any anchor. Now, however, a climber practicing his or her trade outside of the “typical” multi-pitch environment, will have to place different weight on each of the criteria. Other climbing disciplines, whether it is alpine ridges or top-roping or something in between, bring different demands to the anchors we use. Allow the following illustrations to structure a discussion of the figurative weight of each anchor-building consideration in each of the different climbing environments. Realize that this is just one person’s opinion, presented in a very rough fashion, and that the different relative letter sizes are meant to be compared to the other letters in the same discipline only.

|

| Long "enchainments" and ridge traverses put a climber on exposed, yet relatively secure, terrain for much of the day. The skill required to keep the rope handy and apply it to maximum effectiveness is an advanced one. Likewise, the experience and judgement required to apply that skill are often hard-earned. Four climbers died unroped on "easy" terrain in the Sierra in 2012. Anchors will emphasize quickness and ultimatesecurity in the unlikely, yet very high consequence, event of a fall. Ken Etzel Photo |

|

| No one likes to bail. But everyone has to at some point. Leave enough gear, in good rock but keep them simple and clean. |